Reform in name only: Lukashenka's constitutional referendum is a sham

Russia wants constitutional reform to maintain influence, but Lukashenka’s proposals will leave him with a firm grip on power

On 27 February, a referendum on changing the constitution is to be held in Belarus. President Alexander Lukashenka is pushing for amendments that would give him a powerful mechanism for an authoritarian transition of power. The paradox of the situation is that he is unlikely to use this mechanism in the foreseeable future.

The constitutional change would be the third since Lukashenka became president in 1994. The first two changes, both approved by referendum, appeared to be logical steps in the process of establishing a personalist dictatorship: in 1996, Lukashenka significantly expanded his own powers as president and reduced the powers of parliament; and in 2004 he lifted restrictions on the number of presidential terms.

Lukashenka spoke about the third proposed change to the constitution for the first time back in the autumn of 2016, when he announced the need to “create a group of wise men, lawyers who will analyse our fundamental law”. In subsequent years, he returned to the topic from time to time, speaking about the need for constitutional reform, but did not take any specific actions.

In 2020, the issue took on a completely new meaning. After mass protests against the results of the presidential election, Lukashenka began to present his long-standing constitutional initiative as proof of his readiness to enter into a dialogue with society and reform the country. However, the essence of the planned constitutional reform was not revealed: he spoke only in vague terms about the redistribution of power.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

Alexander Lukashenka

Transition plans

Lukashenka outlined his proposals in more concrete terms in February 2021, some five months after the start of protests in August 2020. His plan: to give emergency powers to the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly, a pseudo-parliamentary body, in order to provide a “safety net” in case “the wrong people come to power, and they have different views”.

“We will ensure that not a single hair from you, supporters of the current president, will fall from your head... If this social contract, which we will conclude, is violated, the Assembly will have all the power. You will have it. Even without me,” he told Assembly delegates.

It should be understood that the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly is not a parliament at all. So we are not talking here about a redistribution of powers between the legislative and executive branches of government.

Instead, the Assembly is a forum for Lukashenka’s supporters, including members of the country’s nomenklatura, with representatives of state enterprises, institutes and organisations. The Assembly was formed in secret, with seats simply distributed by the administration. This forum has been called upon to periodically demonstrate ‘nationwide support’ for Lukashenka. However, it does not currently have constitutional powers. With his plan, Lukashenka has de facto proposed guaranteeing his associates a monopoly on power, even bypassing the procedure of a formal election.

Lukashenka’s legacy

It appears Lukashenka started thinking about the future of his family and close supporters, and his political legacy, long ago.

Perhaps he even believed that some day he would retire at a time of his choosing, transferring the presidency to a successor, yet still retaining levers of influence and the status of a kind of ‘leader of the nation’. Lukashenka, it seems, has studied the experience of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president of Kazakhstan who implemented his own authoritarian transition of power in 2019. This seemed successful until January 2022.

Most likely, Lukashenka was interested in the issue of transition only in the long term – he did not plan to retire immediately. That is why, prior to mass protests in 2020, work on the draft of a new Belarusian constitution could not get off the ground: there was simply no need to press the issue.

Alexander Lukashenka

Kremlin interests

Now, the Kremlin has begun to actively lobby for constitutional reform in Belarus. This appears to have been one of the key conditions under which Russia was ready to support the Lukashenka regime as it dealt with the crisis of the 2020 protests.

Initially it was not just a case of Russia pressing for a change to the Belarusian constitution, but also about early parliamentary and presidential elections, which were to take place immediately after the constitutional reform. In August and September 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov publicly referred to promises about elections made by Lukashenka several times when speaking about the political crisis in Belarus. Subsequently, the Kremlin regularly declared support for the constitutional reform as a guarantee of the “modernisation of the political system and normalisation of the situation”. Soon afterwards, however, the topic of early elections completely disappeared from Moscow’s rhetoric.

The Russian authorities have never publicly voiced their wishes regarding the details of Belarus’s constitutional reform. But in general, it is clear what the Kremlin wants to achieve. Putin expects to make the Belarusian political system more predictable and manageable. After all, the events of 2020 highlighted a serious problem for the Kremlin: its interests in Belarus are entirely tied to one person – Lukashenka. There is no one to replace him. The current personalised political system in Belarus simply does not guarantee the emergence of other players and centres of political gravity, which could help Moscow to maintain influence.

In December 2020, The Insider, a Russian independent media outlet, published documents from inside Russia’s presidential administration. The documents, prepared by a department headed by a general in military intelligence, stated that the “massive and deep-seated rejection” of Lukashenka was growing in Belarus, and that this rejection “increasingly embrace[d]” administrative personnel. Therefore, the document advised, the Russian leadership should force Minsk to conduct constitutional reform, which would significantly expand the powers of the Belarusian parliament. In this new parliament, pro-Russian elements should gain as much influence as possible, which “will make the country’s domestic and foreign policy more predictable”.

It is clear that these documents represent just one possible scenario that Putin’s entourage has considered. But they do a good job of illustrating the Kremlin’s logic. In any case, the ultimate goal is the same: Moscow needs guarantees that, even without Lukashenka, Belarus will remain in Russia’s sphere of influence. And the constitutional reform was designed to solve this problem.

The Belarusian Constitution

Popular democracy, Lukashenka-style

In the end, a twofold situation has developed. On the one hand, Lukashenka has been thinking about constitutional reform for a long time. But the topic of the transition of power was of interest to him only in the context of the undetermined ‘distant future’. And he certainly would not want to implement such a complex manoeuvre right now, with the catastrophic election results fresh in people’s memories. As Lukashenka admitted at one meeting: “To be frank, I really don’t need this process.”

On the other hand, the Kremlin continues to push for constitutional reform, and Lukashenka is in no position to quarrel with Russia, his only ally. Therefore, at the end of 2021, he submitted a draft of a new constitution for Belarus.

As expected, the main changes concern the role of the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly. The People’s Assembly is due to receive the constitutional status of “the highest representative body of democracy” in the country and significant powers: the right to impose martial law and a state of emergency; to elect and dismiss judges of the Supreme and Constitutional Courts; and to form the Central Electoral Commission (CEC).

But most importantly, the People’s Assembly will be able to remove the president in the event of a systematic violation of the constitution or treason, as well as consider whether elections are legitimate and give “mandatory instructions to state bodies”.

If Lukashenka decides to leave the presidency, and he moves to head the People’s Assembly, he would still concentrate power in his hands, including the option to remove an objectionable president and to cancel election results, if they are won by “the wrong people”. As a bonus, the former president would receive guarantees of personal immunity from prosecution and life senatorship.

As a democratic carrot, the constitution would reinstate the rule that the president can be elected for no more than two terms. Yet Lukashenka’s own number of terms would be reset to zero: this means he would still reserve the right to be president until 2035.

The transition that won’t happen

The new constitution will give Lukashenka a powerful mechanism for an authoritarian transition of power. The only question is whether he plans to put this mechanism into action in the coming years. Everything indicates that this is not on the cards and the new model of state management will remain on paper only.

Firstly, in the aftermath of 2020, Lukashenka’s regime is in a state of permanent instability. He has lost legitimacy in the eyes of the majority of the population, and the level of rejection of and intolerance towards the authorities in Belarusian society is extremely high. Starting a political transition under these conditions is a huge risk.

Secondly, the January events in Kazakhstan have discredited the very idea of political transition, regardless of its specific circumstances. Kazakhstan’s ‘Bloody January’ has shown that the de jure delegation of power can very quickly lead to the loss of power in reality. And no life-long government posts, such as Nazarbayev held, would change that. Lukashenka can draw only one conclusion from Kazakhstan: power should be kept in one’s own hands for as long as possible.

But if Lukashenka is not going to leave the presidency, then he not only does not need the special powers of the People’s Assembly, but they are dangerous for him. A new centre of power will emerge in the system, which, at least in theory, could limit his own power. To avoid this, the draft constitution spells out the right of Lukashenka (and only him) to simultaneously be both president and chairman of the People’s Assembly. Lukashenka’s deputy head of administration, Olga Chupris, called it “an additional safety net” for the transition period. The circle is closed: in fact, the constitutional reform comes down to the redistribution of powers between the right and left hands of Lukashenka. Nothing will change, either on paper or in reality.

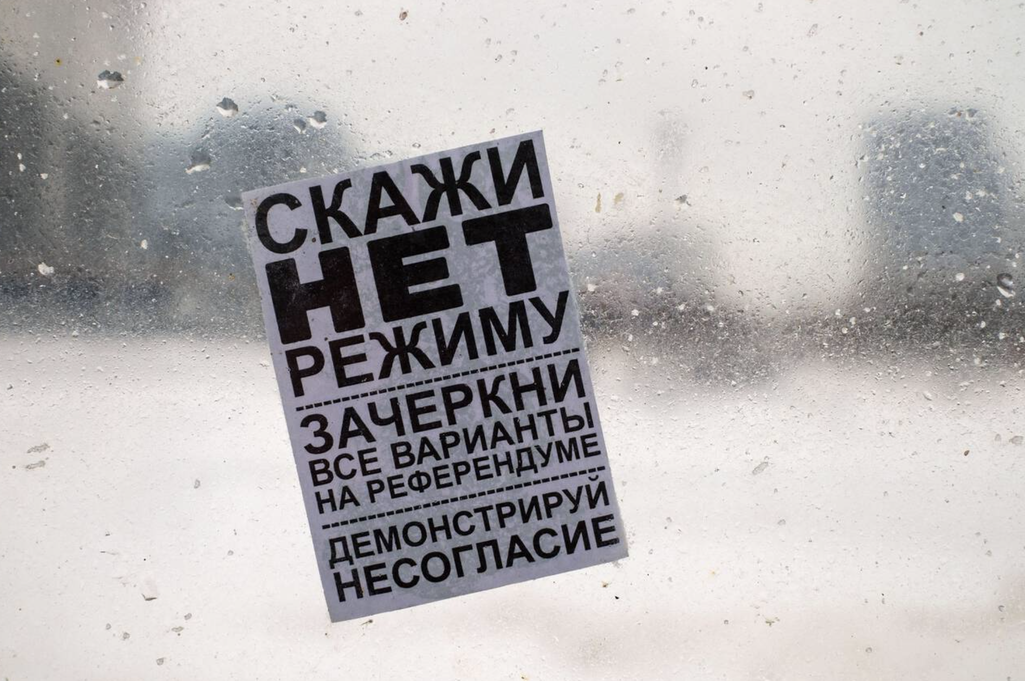

"Say no to the regime": a sticker calls on Belarusian citizens to spoil their ballots at the constitutional referendum

The opposition reacts

The Belarusian opposition considers the forthcoming referendum illegitimate. At the same time, democratic forces urge Belarusians not to boycott the vote, but rather to spoil their ballots. In the opinion of opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, this is the only safe way to express one’s attitude towards the regime and show that the supporters of change are in the majority.

There is currently no talk of organising street protests during the referendum; the opposition is not (yet) planning them. However, Lukashenka himself recently spoke about such a threat – he is well aware that an electoral campaign will lead to a mobilisation in Belarusian society. It is no coincidence that on the day the date of the referendum was announced, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Belarus conducted exercises in suppressing street protests.

The threat of war

After the events in Kazakhstan, many assumed that Lukashenka would refuse to hold a referendum altogether. But he is still proceeding with it. Why?

Several factors seem to have played a role. Firstly, it is important for Lukashenka to at least formally fulfil the promises made to Putin. Of course, it is doubtful that Moscow will be satisfied with this version of constitutional reform, because the referendum will not change anything and all Russian interests in Belarus will continue to be tied to one person. But at least for now, attention will be drawn away from the transition of power. Lukashenka, the story will go, has not refused to hold the referendum. By his own admission, he is simply waiting for the situation to be “quiet”.

Secondly, everyone would unequivocally perceive the cancellation of the referendum as a reaction to Kazakhstan: it would look like a manifestation of fear and weakness. And Lukashenka is trying not to take actions that could be perceived in this way.

Thirdly, the referendum campaign coincided – happily, for the Belarusian regime – with the military and political escalation around Ukraine, in which Belarus, thanks to Lukashenka’s actions, is actively involved. Unscheduled Russian-Belarusian military exercises were announced on the border with Ukraine, the transfer of Russian troops to Belarus began, and the scale of the troop transfer was deliberately concealed. For the first time since gaining independence, there is a real threat of Belarus’s participation in an armed conflict. And Lukashenka himself is skilfully whipping up the atmosphere around this issue: within a week after the announcement of the date of the referendum, he began speaking about a possible war in every speech.

Thus, both for the Belarusians themselves and for the international community, the issue of constitutional referendum has emerged in the shadow of potential serious armed conflict. There was a chance to run a campaign without attracting much attention to it, turning it into a purely technical event. Yet Russian troops on Belarusian territory can be seen as additional insurance for the Lukashenka regime if the referendum leads to protests and destabilisation.

Finally, Lukashenka still has the opportunity to cancel the referendum at the last moment – he has already stressed several times that he can do this in case of war. And today the prospect of war does not look so far-fetched.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.