Empathy

The Politics of Empathy and Race

Empathy's most ardent promoters have keenly felt its absence.

Posted February 12, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

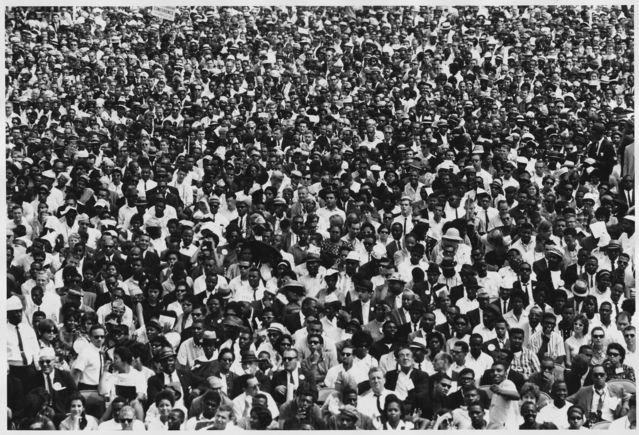

Today we are witnessing a reckoning with the systemic racism and violence inherent in so many American institutions. In recent years, U.S. Senator Cory Booker and President Barack Obama invoked the importance of empathy as a means to heal divides. They are among a number of black intellectuals and civil rights leaders who have spoken out about the importance of developing empathy, a message often directed to white Americans. It is not surprising that empathy’s fiercest promoters are those who have keenly felt its absence.

In 1964, James Baldwin bemoaned the fact that most whites failed to achieve the most basic form of empathy for blacks: to grasp their humanity. Basic empathy entailed the recognition that “in talking to a black man, he is talking to another man like himself.”[1] Martin Luther King Jr., grieved the lack of empathy of white moderates while sitting in a Birmingham jail: “I suppose I should have realized that few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race.”[2]

Social psychologist and civil rights activist Kenneth B. Clark championed empathy over the span of decades. Clark was the first African-American psychologist to graduate from Columbia University in 1940, and two years later he began teaching at The City College of New York.[3] He helped write the social science statement documenting the psychological damage of segregation appended to the 1954 Supreme Court decision to desegregate schools. He and his wife, psychologist Mamie Clark, conducted a series of studies that found that black children in segregated schools preferred playing with white rather than black dolls. The Clarks founded the Northside Treatment Center and Harlem Youth Opportunities to provide psychological and educational services for Harlem youth, in addition to the Metropolitan Applied Research Center to study school desegregation and civil rights.[4]

Clark first called for empathy in a 1965 New York Times opinion piece, “Delusions of the White Liberal.” He explained that liberals were often harder to deal with than bigots, due to their guilt, conflicting loyalties, and acquiescence in the flagrant system of racial injustice.[5] What they lacked, Clark declared, was empathy. Empathy was neither sentimentality nor pity, both of which emanated from a superior position. Empathy instead constituted the basis for mutual understanding that crossed racial lines, rooted in the underlying similarity of the human condition.

But how could this type of empathy be achieved? As a psychologist, Clark was attuned to the mechanisms of defense, repression, and inner resistance that made it difficult for a white person to move beyond their racial bias. Whites, he declared, had to dispense with “the fantasy of aristocracy or superiority,” and the white liberal in particular with “the fantasy of purity,” or the idea of being free of prejudice. In short, the white liberal had to “reconcile his affirmation of racial justice with his visceral racism.”[6]

Whites therefore had to work to “transcend the barriers of their own minds” and to listen with their hearts. Only then would it be possible, Clark imagined, to “respond insofar as he is able with a pure kind of empathy that is raceless, that accepts and understands the frailties and anxieties and weaknesses that all men share, the common predicament of mankind.”[7]

Clark’s calls for empathy became more insistent as American politics shifted toward conservatism. In 1979 he scribbled in a lecture draft, “The only thing that will save us is a universal increase in empathy.” [8] He thought that those with political power lacked empathy, evidenced by their support of the brutal inequalities in American society. Clark even suggested that world leaders might be given a psychoactive pill to enhance their empathic qualities and inspire them to just political action. He believed that competitive, anxiety-prone American culture rewarded the rampant pursuit of one’s own interest. It was therefore imperative for educators to strengthen “man’s empathic capacity.”[9]

Clark placed his hope in the unique human capacity to respond to suffering with intelligence, social sensitivity, and the recognition that despite cultural and racial differences, something was shared. He called this psycho-political foundation for equal rights ”empathic reason.” Empathic reason is the anti-racist capacity to feel and to recognize the principle of the equality of all.

Today we are witnessing the unbearable cost of empathy’s absence in national politics and in American society. To restore empathy to our political discourse is our first challenge, but then we must translate empathy’s moral vision into specific policies to empower those who for so long have endured the evils of racism.

References

[1] James Baldwin, Nathan Glazer, Sidney Hook, Gunnar Mrydal. (1964). Liberalism and the negro: a round-table discussion.” Commentary 37 (3), 38.

[2] Martin Luther King, Jr. (1963, April 16). Letter from a Birmingham jail. http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html

[3] James M. Jones & Thomas F. Pettigrew. (2005). Kenneth B. Clark (1914-2005). American Psychologist 60 (6): 649-651; Richard Severo. (2005, May 2). Kenneth Clark, Who Fought Segregation, Dies. New York Times.

[4] Gerald Markowitz & David Rosner. (1996). Children, Race and Power: Kenneth and Mamie’s Clark’s Northside Center. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

[5] K. Clark. (1965, April 4). “Delusions of the White Liberal.” The New York Times.

[6] K. Clark (1965, 1989). Dark Ghetto: Dilemmas of Social Power. Wesleyan University Press. p. 20, 229.

[7] K. Clark, “Delusions of the White Liberal.”

[8] K. Clark. Unpublished Draft 31 August, 1979. Kenneth B. Clark Papers. Library of Congress.

[9] K. Clark. (1974). Prologue. Pathos of Power. Harper & Row. p. 10.